Vietnam 91: Hanoi |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| * | * | |

Zu einem dieser Fotos fand ich im Internet die folgende Geschichte von Nam Phuong Thi Doan,

die ich hier gerne wiedergebe:

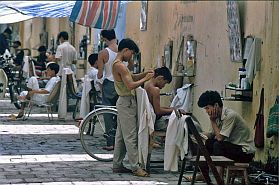

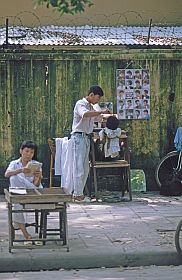

The Number One Scissors of Quang Trung

A glance into the street barbering culture and gentrification process in Hanoi, Vietnam through the story of a street barber and his most faithful customer.

Photo credit: Hans-Peter Grumpe, http://www.hpgrumpe.de My father has been getting his hair cut at the same barber shop for twenty-five years. He said he wouldn’t want to “put his head into anyone else’s hands.” The relationship he has with his barber, cậu Đức, is not only built on trust, but faith. My father, like a lot of people, is obstinate in that way — only faithful to one barber who can give him the service and the style exactly as he wants. The risk of not knowing how his haircut will turn out is just too much to bear. One day, when I was looking for visual documentation of Hanoi after the Đổi Mới period (“Renovation”– economic reforms initiated in 1986 to lead Vietnam towards a socialist-oriented market economy) for a class assignment, I came across a photograph of street barbers on Hanoi’s sidewalk. It was taken in Vietnam between 1991 and 1993 by a German photographer, Mr. Hans-Peter Grumpe, who gathered the world into collections of vivid snapshots. The photograph depicted an ongoing scene of street barbers and their customers on a part of Quang Trung street, between Bà Triệu street and Trần Quốc Toản street, phố cắt tóc (barber street) of the early ’90s. The barber booths looked familiar to me, since street barbering was still a part of the city scene in my time, yet the sight of an entire barber street truly fascinated me. I didn’t think I had ever seen or heard of its existence. The sidewalk was tiled with bricks. The rudiment and openness of the sidewalk, together with the crudeness of the lightly-primed yellow wall, created a barber culture of simplicity and familiarity. Setting up a barber booth didn’t require much: a mirror on the wall, a few pairs of scissors and combs, a wooden chair for customers, and maybe a small sign to beckon passersby. Some barbers invested in self-made hair gel or baby powder to soothe the customer’s newly shaved head. The barbers and customers were dominantly male because they didn’t require trendy hairstyles like women did. (Or, is barbering a performance of masculinity?) A trim or shave was usually quick, simple, and very cheap (less than $1 back in the day). The customers and barbers all had a similar hairstyle in the photo, which I’m guessing was a trendy style in the early ’90s. The loose cami tanks some of the barbers and customers wore were, and still are, a popular Vietnamese-male item of clothing. I remember distinctly seeing my grandfather and father wearing tanks with faded colors growing up. Some others in the photo wore collared shirts and khaki pants, the most casual and comfortable clothes of all time. The vehicles were parked next to their owners; a self-constructed Honda lying in the far left of the photograph reminded me of father’s old Honda Gold Wing, which I had the honor to sit on every morning to school, behind or in front of his steering. My father said when phố cắt tóc existed, he always went to booth 23, the booth of cậu Đức. “The number of years I’ve known cậu Đức is more than the years I’ve known you,” he said. After 1986, a lot of spontaneous and self-sustaining trading streets like the barber street were birthed. Even though the state still played a decision-making role in the economy, private businesses and small-sized cooperatives were allowed to thrive, and people were encouraged to use creativity in economic innovation. When it first came together, the barber street was busy all the time. Barbers from different corners around and outside the city gathered at the area, creating some sort of a barber craft village. Customers ranged from monks and students to soldiers and police officers. My father was a news reporter at the time, and going to the barber street was one of the delightful habits of his youth. Barbers and customers became friends; friendship and partnership sparked in the most spontaneous, simple, and self-operated form of economic exchange. Having their booths on the sidewalk helped the barbers create an invitation of participation to the passersby — they came from all walks of life and brought with them stories of the universe. The economic exchange became social exchange, which sometimes turned into a more long-lasting connection just like that between Father and cậu Đức. The barber street went from word-of-mouth to the news, giving reputation to a lot of amateur barbers. Barbering competitions also happened among the most skillful and enthusiastic barbers, which generated a cheerful atmosphere to the barber street. To most of the street barbers, cutting hair was a job but also a hobby: they got to practice their scissors skills while sharing daily gags with the customers. Despite its popularity, the barber street was expunged when gentrification and modernization knocked on the door of the city in the late ’90s and early ‘2000s. No sooner had Vietnam opened up to the world than the economy blossomed; sumptuous vehicles and voguish clothes started appearing on the streets. Street vendors were considered a stain to the cityscape as the living standards rose higher and buildings and storefronts were growing like mushrooms after the rain. The barbers diverged from Quang Trung street and scattered all around. Some of them opened their own salons, while some switched to other jobs. Father lost contact with cậu Đức. It was not until a long time after I was born that they found each other again, when father stumbled into a small barber shop on 22 Hàng Ngang called “Quang Trung Đệ Nhất Kéo” (The number-one scissors of Quang Trung). He recognized it right away because cậu Đức won the first prize in the barbering competition on Quang Trung street back in the heyday of street barbering. The life of cậu Đức was a series of driftings. From the best barber booth at Quang Trung, he drifted to a small corner of Trần Quốc Toản street, and then to a tiny alley of Bà Triệu street. He has always been faithful to the sidewalk. He didn’t want to open a salon with fancy services like most barbers ended up doing. Despite having drifted to different corners of the city in difficult circumstances, cậu Đức still managed to continue barbering. He cuts hair like a hobby, a pleasant ritual for himself, and a job to support his family. To him, barbering is a means of living but also something like fate. He is destined to be a barber. A lot of barbers drifted and changed their careers, but cậu Đức was too attached to barbering to give it up. His customers changed over the years, from rich gentlemen and officials to factory workers. They also drifted to different corners of life: some made a fortune and became important, some went to jail. The regulars like my father truly made it worthwhile for cậu Đức. In an urban timespan of constant twists and turns and changes and revisions, the long-term friendships with customers were the connecting anchors in his life. People come and go, shops appear and disappear, the sidewalk is no longer free — is cậu Đức sad? No, he has never been sad because drifting is natural and changing is inevitable. The barber street and street vendors were an image of a poor country rising from agriculture to market economy. The sidewalk culture might not be destined to remain forever on the front of the urban life of Hanoi, yet it will forever remain in the nostalgia and remembrance of generations who didn’t grow up in privilege. Cậu Đức is content, because he can keep barbering and meeting people. He used the money he earned from barbering to help raise one of his siblings, who later got married to an American. Now, he has nieces and nephews from the U.S. running around in his modest barber shop. My father sometimes saw the children poking out here and there, and the married sibling reading English novels in the shop. He is quite sure that cậu Đức is pleased and happy. Near my house there are a lot of high-quality salons bright and open until midnight, but Father refused to go to them. He is estranged from that “luxury” culture. He said that it was unnecessary and absurd — who needs their head massaged or their nails done? All they really need is a fifteen-minute haircut. Father agrees that it might be the right call to clear out the sidewalk as a part of urban planning. He just wonders about the drifting destinies of the street vendors and their customers. I, however, do think that the sidewalk culture, along with its non-bourgie essence, is a part of our city’s identity. It’s hard to imagine an ecosystem of economic and social exchange solely existing behind storefronts. Until when will the sidewalk be able to claim its public, and the city to consider the drifting and displaced constituencies on its growing agenda? With kind permission: Nam Phuong Thi Doan Quelle: https://namphuongthidoan.medium.com/the-number-one-scissors-of-quang-trung-bc5e1b82f81d hier: deutsche Übersetzung |

|

© Hans-Peter Grumpe |

Bilder mit * wurden 2021 hinzugefügt